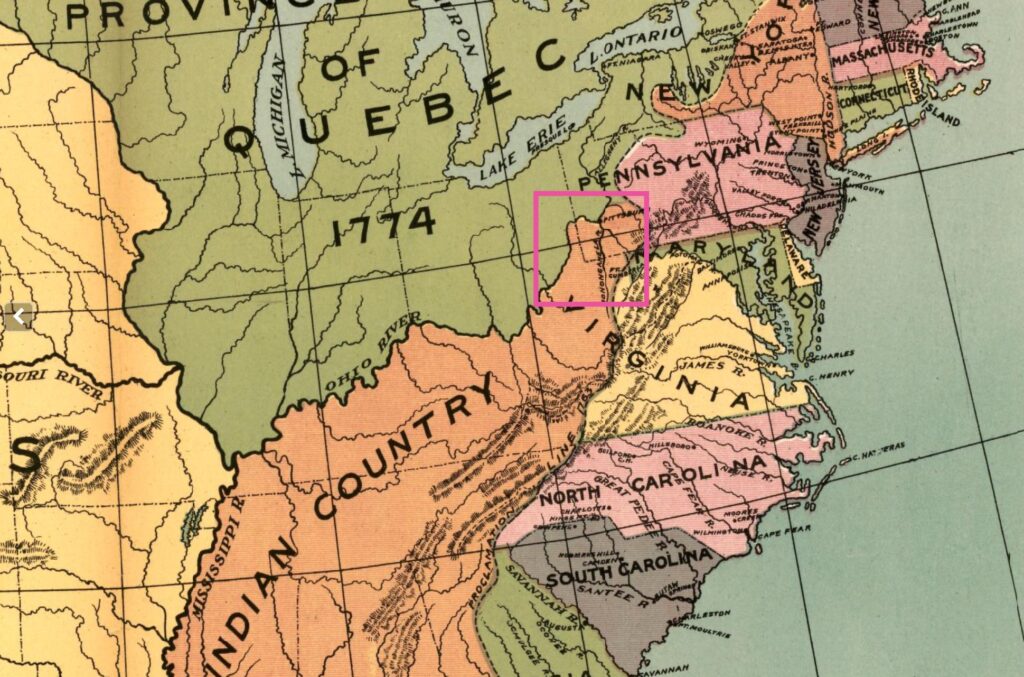

In the decade after the French and Indian War, the frontier between Fort Pitt and the future site of Wheeling buzzed with uncertainty—half promise, half threat. This was contested ground, scarred by past conflict and rich with opportunity, and nobody knew that better than George Washington. (I know some people don’t like to think of America’s first president as a savvy land tycoon, but I personally think moving beyond the myth humanizes him.)

Gilbert Imlay’s A Topographical Description of the Western Territory of North Americadescribed a “Mingo town” about seventy miles downriver from Fort Pitt and upriver from the future site of Wheeling. When George Washington passed through the area in 1770 on a surveying expedition, he recorded twenty cabins, seventy inhabitants, and members of six tribal nations living in what Anglo-Europeans had labeled Mingo Town.[1] He wasn’t sightseeing—he was assessing value. As a veteran and rising political figure, Washington was lobbying for land grants on behalf of those who had served Virginia in the Seven Years’ War (known in North America as the French and Indian War) and used this journey to evaluate opportunities firsthand.

Like many colonial elites, Washington had a personal stake in the West. He had fought for it. And now he wanted to claim it. Postwar leaders like him were lobbying to secure frontier land grants for veterans, and his expedition was, in part, a reconnaissance mission, for land, for leverage, and for perhaps even legacy.

Washington’s journal also records another site further downstream: a hunting camp known as Grapevine Town, situated approximately thirty-eight miles beyond Mingo Town near Wheeling Creek. His account suggests that this was a seasonal camp, likely used by male hunters and supported by a small number of women who traveled with them.

One notable anecdote from his journey captures the early colonial spread of misinformation. Washington reported hearing rumors that two traders had been killed by Native inhabitants of Grapevine Town. Upon investigating, however, it was discovered that only one man had died, and he had drowned while attempting to ford the river at an ill-advised crossing.[2]

It was during this same expedition that Washington encountered the Seneca leader Guyasuta (also spelled Kiasutha). Nearly two decades earlier, Guyasuta had served as a guide and intermediary during Washington’s 1753 diplomatic mission to Fort Le Boeuf, where he was tasked with delivering a message from the British crown advising the French to vacate contested territory in the Ohio Country.

By the time of the Seven Years’ War, however, Guyasuta fought on the side of the French. He was among those who triumphed at Braddock’s defeat in 1755—a battle in which George Washington was one of the few British survivors. Their paths, once briefly aligned, had diverged.

In the years to come, Guyasuta would play a crucial diplomatic role in Lord Dunmore’s War, working—like Lenape leader White Eyes—to keep the Six Nations neutral amid rising tensions between Native nations and Anglo-American settlers.

By the time of his Ohio River journey, Washington was no stranger to legal complexities. He knew the tangled mess of colonial land claims—the overlapping patents, vague charters, and surveying disputes—because he needed that knowledge to secure his own investments. When Pennsylvania opened lands west of the Alleghenies in 1769, Washington moved quickly, working through William Crawford to negotiate for plots in the Kanawha region.

By 1783, half of Bedford Country, Pennsylvania, was owned by speculators who had never resided there. The people who did live there—actual settlers, tenant farmers, tradesmen—often held nothing at all. [3] In Washington County, where ownership claims were tied up in the border dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia, uncertainty reigned. Meanwhile, neighboring Washington County’s 1781 tax list shows the opposite. Unlike Bedford County, Washington County was in the contested border zone between Pennsylvania and Virginia. Pennsylvania’s Land Office may have opened up the lands for settlement, but the political impediments to ownership remained.

Washington’s recording of Mingo Town and Grapevine Town, along with his meeting with the Guyasuta, reveals that although many Native communities did not occupy these Ohio River Valley sites year-round, they were far from vacant. These places functioned as seasonal settlements, hunting camps, and intertribal gathering points. To Washington, these sites appeared sparsely inhabited, and thus ripe for future claims. But for Native nations, they were part of a broader cultural and territorial landscape—a living network of mobility, memory, and meaning that defied colonial property lines.

The line between ownership and occupation was murky. For colonial elites, land meant power. For Native peoples, it meant survival. And for settlers, tenant farmers, and former soldiers hoping to claim a foothold in the West, it meant navigating broken promises, legal confusion, and the quiet advance of wagons, boots, and axes—moving tree by tree, acre by acre.

[1] W.H. Hunter. “The Pathfinders of Jefferson County.” Ohio Archeological and Historical Quarterly 6, no. 2 & 3 (April & July 1898). 115.

[2] Washington. “The Writings of George Washington; Being His Correspondence, Addresses, Messages, and Other Papers, Official and Private, Selected and Published from the Original Manuscripts with a Life of the Author, Notes and Illustrations.” 523.

[3] Jackson Turner Main. Social Structure of Revolutionary America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Leave a Reply