The English were traders on the Ohio River by the early eighteenth century, but the colonies were largely concentrated along the Atlantic coast. In 1747, the combined lobbying of Virginia planters and London stockholders finally paid off when King George II approved the charter granting the Ohio Company of Virginia 200,000 acres of land in what is now West Virginia, western Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Ohio.[1] Frontiersman Christopher Gist was employed to survey the land and negotiate with the Native tribes.

By 1750, English settlers largely controlled the eastern seaboard. Many of the Native tribes who had once lived there had since been pushed westward following a series of broken alliances, wars, and forced removals. The Ohio River Valley for the moment remained untouched from European influences.

While the colonial government believed it could contend with the peoples that lived within the mysterious barrier of dense trees and vegetation that separated the coastal plain from the interior, it did not realize that the French would react furiously to no longer having a broad line of demarcation between their English rivals and their operations. However, the first sign of border contention, in a sign of conflict to come, appeared in 1754 when Pennsylvania Governor Hamilton wrote Governor Dinwiddie notifying him that Virginia’s intended fort location at present-day Pittsburg was within what Pennsylvania considered its chartered territory.

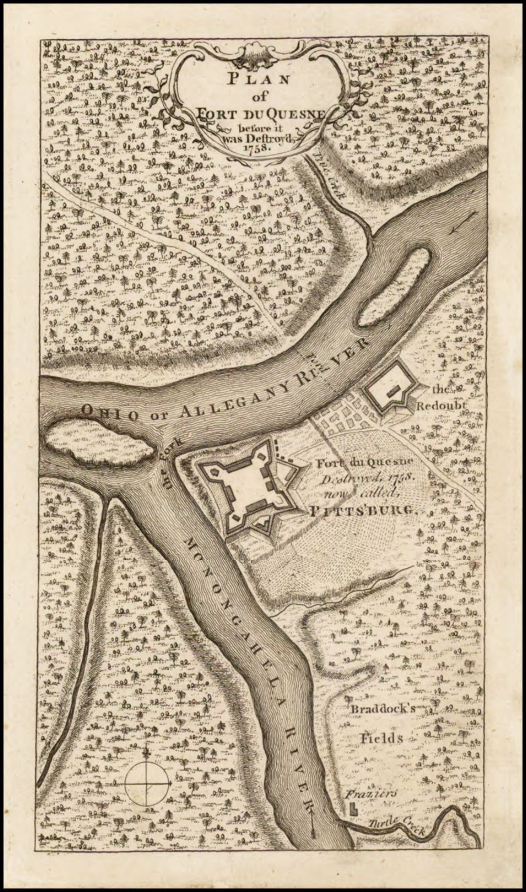

Gist chose the site of the Ohio Company’s fort at the fork of the Ohio River, upriver of the Native trading settlement known as Logstown. Despite the early escalating inter-colony tensions , it was the French with Native support, not Pennsylvania, who interfered with the Virginian’s building project. The French led alliance co-opted the Ohio Company’s fort site for what became Fort Duquesne. At that time, La Belle Rivière (the French name for the Ohio River) remained firmly outside English control.

During the Seven Years’ War, Fort Duquesne was a hub of terror for European colonists in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. Mary Jemison, who alone survived the fate of the rest of her relatively newly immigrated Scots-Irish settler family from an attack by Shawnee and French on their western Pennsylvania squatter’s settlement, recounted being brought to Fort Duquesne.

Mary Jemison remembered that among the hoops that held the scalps of her family and neighbors, her mother’s stood out distinctly due to her striking red hair. Just downriver of the fort, she later recalled seeing the burnt heads, limbs, and the other fragments of white-skinned bodies.[3]

James Smith, another colonial captive taken by the Lenape, reported being brought to Fort Duquesne after his capture. Like Jemison, Smith was spared because he was selected for adoption into a Native community. He was present within the fort during General Braddock’s disastrous 1755 campaign against French and Native forces. According to Smith, every prisoner captured during the battle was executed shortly thereafter.[4] Overall, British colonial forces lost roughly two-thirds of the 1,300 men who had marched northwest with Braddock.

In the aftermath of Braddock’s 1755 defeat, Fort Duquesne emerged as a potent symbol of French and Native strength in the contested Ohio Valley. For English settlers across western Pennsylvania, the fort’s presence cast a long shadow: raids became a constant threat, and the fear of violence hung over daily life. While large-scale British offensives stalled, smaller skirmishes and assaults on frontier homesteads became routine. For the next three years, Fort Duquesne functioned not only as a strategic outpost but also as a launchpad for psychological warfare, spreading terror throughout the Anglo-American backcountry.

When the outnumbered French intentionally blew up the Fort by igniting its gunpowder reserves in 1758, a new chapter in North American colonialism began. General Stanwix ordered a new fort built atop the ruins of Fort Duquesne in 1759, now to be known as Fort Pitt.

[1] “Guide to the Ohio Company Papers, 1736-1813 DAR.1925.02.” ULS Digital Archives. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3AUS-PPiU-dar192502/viewer.

[2] Stanford University Libraries. A Map of the British and French Dominions in North America with the Roads, Distances, Limits, and Extent of the Settlements. London: uJohn Mitchell, 1755. Accessed June 14, 2025. https://purl.stanford.edu/cm845jc4820.

[3] Seaver, James E. Life of Mary Jemison: Deh-he-w̃-mis. Buffalo, N.Y: Print. House of Matthews Bros. & Bryant, 1886. 56.

[4] Smith, James. Captives Among the Indians: First-hand Narratives of Indian Wars, Customs, Tortures, and Habits of Life During Colonial Times. Edited by Horace Kephart. New York: Outing Publishing Company, 1915. https://archive.org/details/captivesamongind00keph/page/22/mode/2up.

[5] Pyle, Howard. “Braddock’s defeat, Battle of Monongahela.” Painting. [ca. 1890–1896]. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/c247gh00d (accessed June 15, 2025).

Leave a Reply